The History of Pascal

The Pascal programming language was designed to promote good programming practices and properly structured programming and data structures. It was also specifically designed to be a small and efficient language that quickly produces efficiently generated code. Pascal is characterized as being strongly typed and type safe. This means that all variables have a specific type (integer, string, etc.), and the compiler enforces that the type is respected and only converted through explicit conversions. Pascal favors the use of English language keywords to create a language that is as easy for a human to read as for a computer.

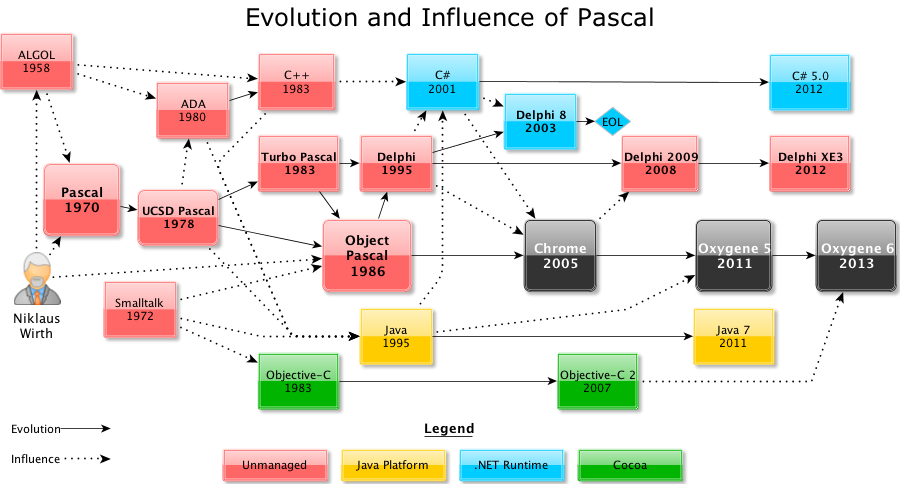

Niklaus Wirth started designing Pascal in 1968, publishing it in 1970. It was named in honor of French mathematician and philosopher Blaise Pascal. When designing Pascal, Wirth took inspiration from ALGOL (specifically ALGOL-60 and his own ALGOL-W), as well as Simula 67. This inspiration is evident in its use of English keywords (Begin, End, Procedure, etc.) and some of the primitive data types (real, integer, array, etc.). ALGOL also uses the := operator to differentiate setting a value instead of comparing values (which just uses the = operator).

In 1970, when Pascal was originally published, the concept of structured programming had just recently become popular. Because of Pascal’s efficiency, clean design and emphasis on structure, many schools adopted it as the de facto language for generations of students learning programming. Those students went on to design and influence other modern languages, taking what they learned from Pascal with them. The first Pascal compiler was designed in Zürich for the CDC 6000 series mainframe computer family. Throughout the 1970s, Pascal was ported to a variety of different mainframe systems, including the PDP-11, ICL 1900 and IBM System/370.

In 1978, UCSD Pascal was introduced, which offered Strings and Units and introduced p-Code and the p-System virtual machine. This architecture was a key influence on Java, its byte code and virtual machine. In the early 1980s it was ported to Apple II and Apple III computers, providing a structured alternative to the default BASIC interpreters. UCSD Pascal remained the dominant Pascal on most platforms until the rise of Turbo Pascal.

In the early 1980s, Anders Hejlsberg wrote the Blue Label Pascal compiler for the Nascom-2. Blue Label Pascal was purchased by Borland, renamed Turbo Pascal, and ported to CP/M, IBM PC and the Macintosh. The 1980s saw a lot of evolution and growth for Turbo Pascal. This included the introduction of unit files, which made Pascal a modular language. Prior to the introduction of units, all source code was in a single source file. Units allowed source code to be divided between multiple source files that referenced each other. The other advantage of units was the concept of namespaces — they allowed duplicate identifiers to exist in two different units since the unit name provided a way to differentiate the identifiers. Units also allowed for a greater degree of code reuse. During compilation, all the units are compiled into a single binary or object file.

Object Pascal

In 1985, Apple consulted with Niklaus Wirth and took influence from SmallTalk to add Object Oriented extensions to Pascal. This new language was called Object Pascal. Features of Object Pascal were integrated into Mac Pascal and Lisa Pascal. In 1986, Anders Hejlsberg also integrated Object Pascal features into Turbo Pascal. Also at this time, Microsoft implemented their short-lived Pascal compilers.

The evolution of Pascal to Object Pascal is similar to the evolution of C to C++. Both started as a structured procedural language and then, through a number of extensions, gained Object Oriented Programming concepts. The Object Pascal extensions were less radical than the C++ extensions; because of this, Object Pascal is frequently simply referred to as Pascal, while C++ is rarely referred to as C.

During the late 1980s with Turbo Pascal’s aggressive pricing leading the way, Pascal greatly increased in popularity on both the Apple and PC platforms. BASIC developers were upgrading to Pascal in search of a structured programming replacement. Other programmers were moving to Pascal for a faster compiler, type safety and Object Oriented extensions.

In the 1990s, Borland decided they wanted more elaborate Object Oriented Extensions for their new Delphi product. Anders Hejlsberg once again redesigned their Pascal based on Apple’s Object Pascal draft standard. This new derivate language is referred to as Object Pascal or the Delphi Programming Language. It included a reference-based object model, virtual constructors and destructors, as well as properties. Also notably, Delphi introduced the component model, which made use of run-time type information (RTTI). The component model took code reuse to the next level by allowing drag and drop inclusion of reusable code, including visual elements. The RTTI allowed for design time configuration through published properties and WYSIWYG editing for visual components.

Delphi

Delphi was released in 1995 and made up of five distinct parts: The IDE, the compiler, the RTL, the VCL and the BDE. The Delphi Integrated Development Environment (IDE) includes the code editor, integrated debugger, visual designer, component palette and property editor.

The compiler is integrated into the IDE and also accessible from the command line. It is a linking compiler, going straight from source files to native executables or DLL’s.

The Delphi Run Time Library (RTL) includes all the non-visual libraries used in Delphi applications. It is made up of reusable classes and procedural code. It includes wrappers for common Windows API calls.

The Visual Component Library (VCL) is the collection of visual components included with Delphi. It actually includes non-visual and visual components. The difference between the VCL and the RTL is that the VCL can be installed on the component palette in the IDE while the RTL cannot.

The Borland Database Engine (BDE) is a database abstraction layer to work with different databases, including the Paradox and Interbase databases that ship with Delphi. The BDE evolved into other data access libraries and classes that are included in the VCL and RTL.

In parallel, the Free Pascal compiler was developed as a free and open source compiler implementation of the same Object Pascal language used in Delphi. It supports most of the features, and includes an abstraction library similar to the VCL and RTL. It supports multiple CPU’s and platforms, including x86, AMD64, ARM, Linux, Windows, iOS and OS X.

Also introduced in 1995 was the Java programming language and framework from Sun Microsystems. Java's design was influenced by C/C++ and Pascal/Object Pascal as well as other languages. Its syntax is very similar to C in that it favors punctuation over English keywords.

Java is the language, the framework and the platform that the language is compiled for. Unlike Pascal, which compiles to native machine code for the platform that it runs on, Java produces byte-code that runs in the Java Virtual Machine. Then through a process called JIT (Just-In-Time) Compiling, the byte-code is compiled to native machine code when it is run. This allows Java programs to run on any platform that has a Java Virtual Machine (JVM) designed for it – thus giving Java a greater reach of platforms to run on. JVMs were implemented on most popular platforms, and some hardware engineers even implemented a JVM on a chip. One of the most distinguishing characteristics of Java is that it uses a garbage collecting memory manager.

Borland started a skunk-works project to port Delphi to the Java platform, which would have allowed programs written in the Delphi dialect of Object Pascal to run on any platform with a JVM. It would also have positioned Pascal as the first language, besides the Java language, to run on the JVM. After much exploration, this project was abandoned. A big reason for that was the difficulty of imposing an abstraction layer compatible with the VCL & RTL on the Java platform.

Instead, Borland ported their Delphi IDE and language to the Linux platform. They released Kylix in 2001, a new version of the Delphi IDE and compiler that ran exclusively under a few versions of x86 Linux. The Kylix compiler only built native binaries for Linux and could not cross-compile for Windows. Borland introduced a cross-platform version of the VCL that was called CLX (pronounced "Clicks"). CLX was based on the VCL and was very similar to it, but it was not exactly like the VCL. Behind the scenes, the CLX made use of the QT widget library (by Trolltech, later acquired by Nokia) on both Windows and Linux. The idea was that a VCL application could be migrated to CLX and then be compiled by Delphi or Kylix to create a multi-platform application from the same code.

The reality was that the VCL and CLX libraries were similar, but not exactly the same. With more complex applications, the differences in the behavior of the libraries became more evident and the promise of multi-platform code sharing crumbled. Also, the Linux platform evolves faster and is more divergent than the Windows platform. Since Borland was maintaining two different IDEs and compilers (one for Windows and one for Linux), they were not able to keep up with the new releases of Linux or support all the different flavors of Linux that were available. Community and open source efforts were made to expand Kylix’s support, but after just three versions it was discontinued, with the last version released in 2002.

In 2001, Microsoft released its C# programming language and .NET Framework in response to Sun’s Java. It was heavily influenced by Java. Anders Hejlsberg was the chief architect of C#, and the language was also strongly influenced by his experience in designing Delphi. When later questioned about the similarities and influences he said: “Good ideas don’t just go away”.

C# and the .NET Framework are very similar to Java and the Java framework. C# makes use of the C syntax, but the object/component model is more similar to what is found in Delphi or Object Pascal. C# compiles to the Intermediate Language (IL) which runs on the .NET Framework and goes through a JIT process to produce the native code that runs on the hardware. The .NET Framework also has a garbage collecting automatic memory manager very similar to what is offered by Java.

A significant difference between the .NET Framework and Java or other platforms that preceded it was that the Visual Studio IDE was an integral part of the .NET platform and development experience. Java does not have an official IDE and other platforms like Windows and Linux have a variety of IDEs, languages and development tools that support them. This means that when necessary, a new version of the Visual Studio IDE is released to support the new features in the .NET Framework. However, the Visual Studio IDE is not required for .NET development, as the C# compiler and everything else necessary is actually shipped for free with the .NET Framework SDK.

Another significant difference between the Java platform and the .NET platform is that the .NET platform was designed from the ground up to allow for multiple languages to run on it. When the .NET Framework was released, Microsoft provided both C# and VB.NET as languages for development on the .NET Framework. Other languages followed close behind. Some of those languages were adapted from existing languages, while others were entirely new languages.

Borland saw this openness of the .NET platform as another opportunity for them to port their Delphi product to a new platform. The idea this time was to have both platforms supported from the same IDE (unlike with the Kylix IDE on Linux), so they could focus their resources instead of dividing them. The existing Delphi IDE was not suited for hosting the new .NET designers, so a new IDE was created with plans of it hosting both the existing VCL designers and the .NET designers.

In order to support the .NET framework with the new version of the Delphi language, a number of enhancements were added to the language. These new features migrated from Delphi for .NET back into Delphi for Win32 to maintain code compatibility between the two languages. Another way to maintain code compatibility was the introduction of the VCL.NET and RTL.NET. These are .NET versions of the two libraries that map to the .NET framework behind the scenes, but have similar interfaces as the existing VCL and RTL libraries. There were now three versions of the VCL: VCL (for Win32), CLX (cross-platform) and VCL.NET (for .NET). All three were similar, but not exactly the same. This means that events might fire in different orders, or other slightly different behaviors.

The first release of the new IDE in 2003 was Delphi 8, which only supported the .NET compiler and the .NET designers. Future releases of Delphi with the new IDE had the option of supporting Delphi for .NET and Delphi for Win32. Delphi for .NET was supported for 3 releases, through to Delphi 2007, before being retired. The three big problems with Delphi for .NET were that it was not able to keep up with the changes to the .NET Framework and was typically a version behind, a lot of the .NET tools were not available outside of the Visual Studio IDE, and even though substantial effort was put into allowing shared source multi-platform applications, the majority of applications were only targeting one platform or the other, and not both.

Oxygene

In 2005, and in response to the direction Delphi for .NET was going, RemObjects Software’s marc hoffman and Carlo Kok decided to create a new Object Pascal for .NET. Instead of focusing on backwards compatibility and all the baggage that brings, they instead focused on creating an Object Pascal that fully supported the .NET Framework. Called Chrome (and later renamed Oxygene), this new language was based on Object Pascal, but took inspiration from Turbo Pascal, the Delphi programming language and C#. The result was a language that was mostly compatible with Delphi’s dialect of Object Pascal, but not 100%. A big part of the lack of compatibility was that no effort was made to port the VCL. Instead, Oxygene used the visual components and libraries that came with the .NET framework.

Instead of creating a new IDE, Oxygene was integrated into the Visual Studio IDE. It is also integrated into the MonoDevelop IDE, which is a cross-platform, open source IDE that makes use of the Mono Framework. This allowed it to take advantage of all the tools available on the .NET platforms, as well as all the latest innovations to the .NET platform since they are always immediately supported in Visual Studio. Another significant difference between Oxygene and Delphi is that Oxygene embraces the platform as closely as possible without the inclusion of an abstraction layer.

Oxygene is made up of three parts: The compiler, the integration with the IDE and a few supporting libraries.

The compiler is the core of Oxygene. It compiles the source files into the Intermediary Language (IL) assemblies to be executed on the .NET Framework.

Modern IDEs provide a rich code editing environment, visually indicating classes, members and method parameters, as well as the location of errors in the source files. Another important part of the IDE integration is that the visual designers generate code behind the scenes. The IDE integration allows the IDE to generate this code in Object Pascal so that the Oxygene compiler can compile it.

There are a few support libraries used by Oxygene. They are not an abstraction layer like the VCL and RTL provide, but instead add additional functionality like Aspect Oriented Programming.

While Oxygene was first designed to target the .NET framework, it also had first class support for the Mono Framework. The Mono Framework is an open source, cross-platform implementation of the .NET Framework. It is primarily used to add Linux and Macintosh support for .NET applications, but is supported on a variety of other platforms, including iOS, Android, Windows and a number of consoles. Oxygene allowed applications to be compiled and debugged against the Mono framework right from the Visual Studio or MonoDevelop IDEs to ensure compatibility.

In 2008, Delphi for .NET reached the end of life. Instead of abandoning the .NET platform though, Embarcadero (the company that purchased Delphi and related products from Borland) decided to license the Oxygene language from RemObjects and ship it as Embarcadero Prism to provide an Object Pascal for .NET solution. While legacy Delphi for .NET applications are not compatible with Prism, applications built with Prism and Oxygene are able to take full advantage of all the features of the latest version of the .NET Framework. Through the use of cleverly written libraries and compatibility flags, some non-user interface code can be shared between the Delphi and Oxygene compilers.

In 2011, RemObjects Software took their Oxygene dialect of Object Pascal where no Pascal had successfully gone before: to the Java Platform. Code-named “Cooper”, the Oxygene for Java compiler compiles the same code as Oxygene for .NET, but for the Java platform. Again, they applied the same philosophy of not bringing any technical baggage from other platforms in the form of abstraction layers, and instead focused on embracing the platform fully and completely. As a result, Oxygene for Java is fully suited for creating applications that target Android or any other platform supported by Java. The API calls are the same as they would be with Java, only using the friendlier Oxygene syntax.

In 2013, Oxygene gained support for compiling for the Objective-C runtime and its underlying C RTL.

Today

Today Pascal is alive, well and going strong. The language that started out for educational purposes has grown and evolved with features of a modern language and with versions for any platform. Features include Generics, Anonymous Methods, Aspect Oriented Programming, Language Integrated Query (LINQ), Parallel Support, Class Contracts, Events, Exceptions and Properties.

RemObject’s Oxygene now compiles to all major development platforms in use today: The Microsoft .NET Framework (including Silverlight, WinRT and the Mono Framework), the Java Platform (including Android) and Cocoa (as used on Mac and iOS). This opens Pascal up to every common platform today, and the largest possible collection of libraries and frameworks available. Java and .NET are the most common platforms used in Enterprise application development, especially enterprise web development. Additionally, Oxygene specifically targets mobile platforms, including iOS devices (iPhone, iPad, etc.), Android, Windows Phone and BlackBerry. Pascal is one of the most widely known languages today.

All trademarks are property of their respective owners and are used for identification purposes only.

Check out RemObjects C#, Swift or Iodine (Java)!